Genetics Part II: Gene Expression

Although the last blog covered the fundamentals of genetics, it largely ignored the process by which genetic code is converted into a biological process. The aim of this blog is to describe this conversion process in some detail.

Gene expression

Gene expression describes the conversion of genetic information into some product involved in a biological process. There are two steps to gene expression: 1) transcription, and 2) translation.

Transcription

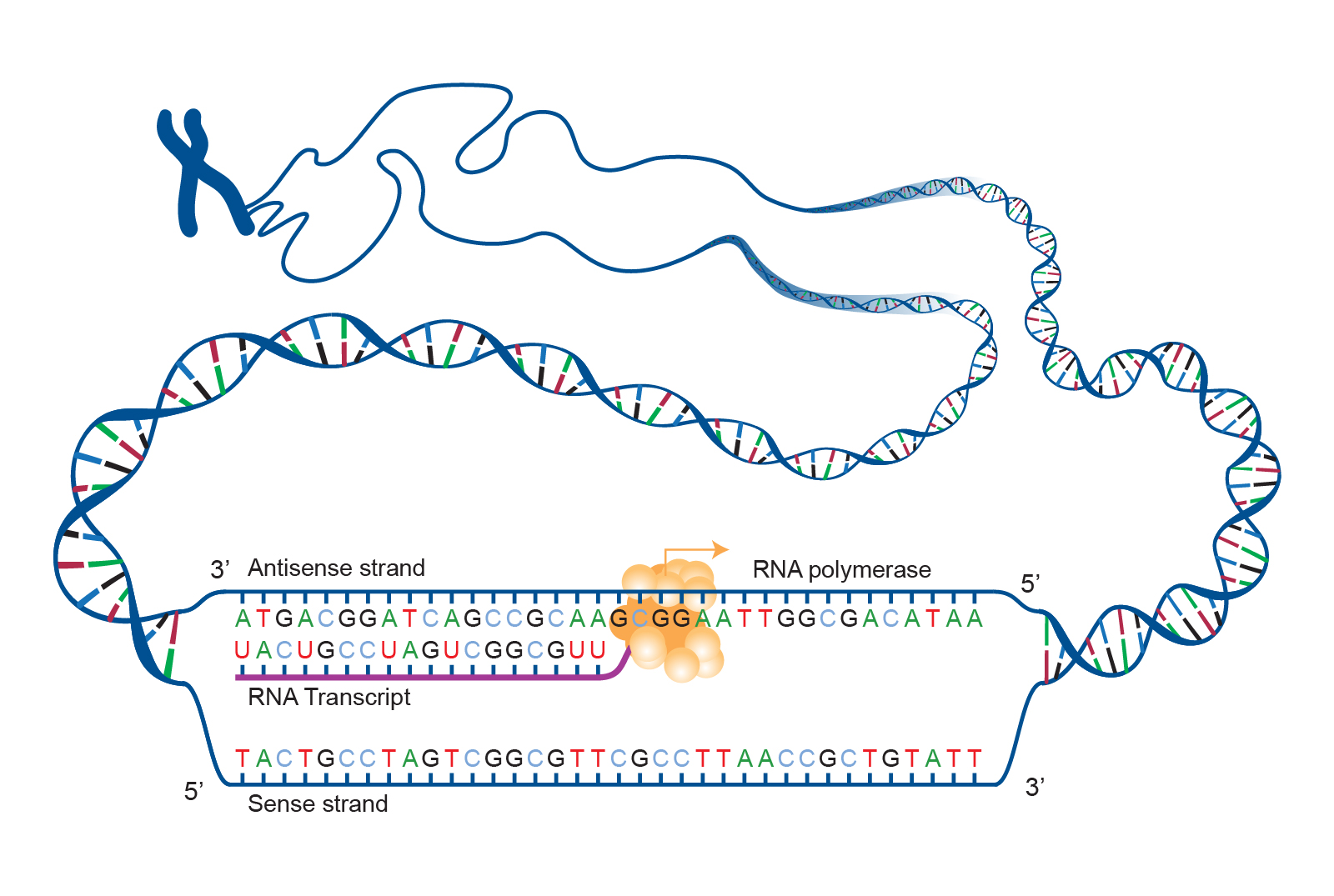

Transcription is where a separate copy of the gene of interest is created (figure 1). The gene copy is made from ribonucleic acid (RNA), a molecule which is similar to DNA but with some important differences:

- It consists of only a single strand that is complementary to the DNA sequence of the gene.

- The thymine (T) base normally found in DNA is replaced by uracil (U).

The machinery responsible for making this RNA gene copy is called RNA polymerase (the -ase suffix denotes an enzyme, a protein involved in biochemical reactions, and the polymer- prefix indicates that this biochemical reaction involves polymerization of RNA molecules).

After this RNA copy is synthesized, it is transported from inside the nucleus to the cytoplasm where the second stage of gene expression occurs (translation).

Because the RNA copy is shuttled from one cell compartment to another, it is known as messenger RNA (mRNA). This is to distinguish it from the other types of RNA, some of which will be discussed later in this blog.

|

|---|

| Figure 1. Overview of transcription. Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute |

Translation

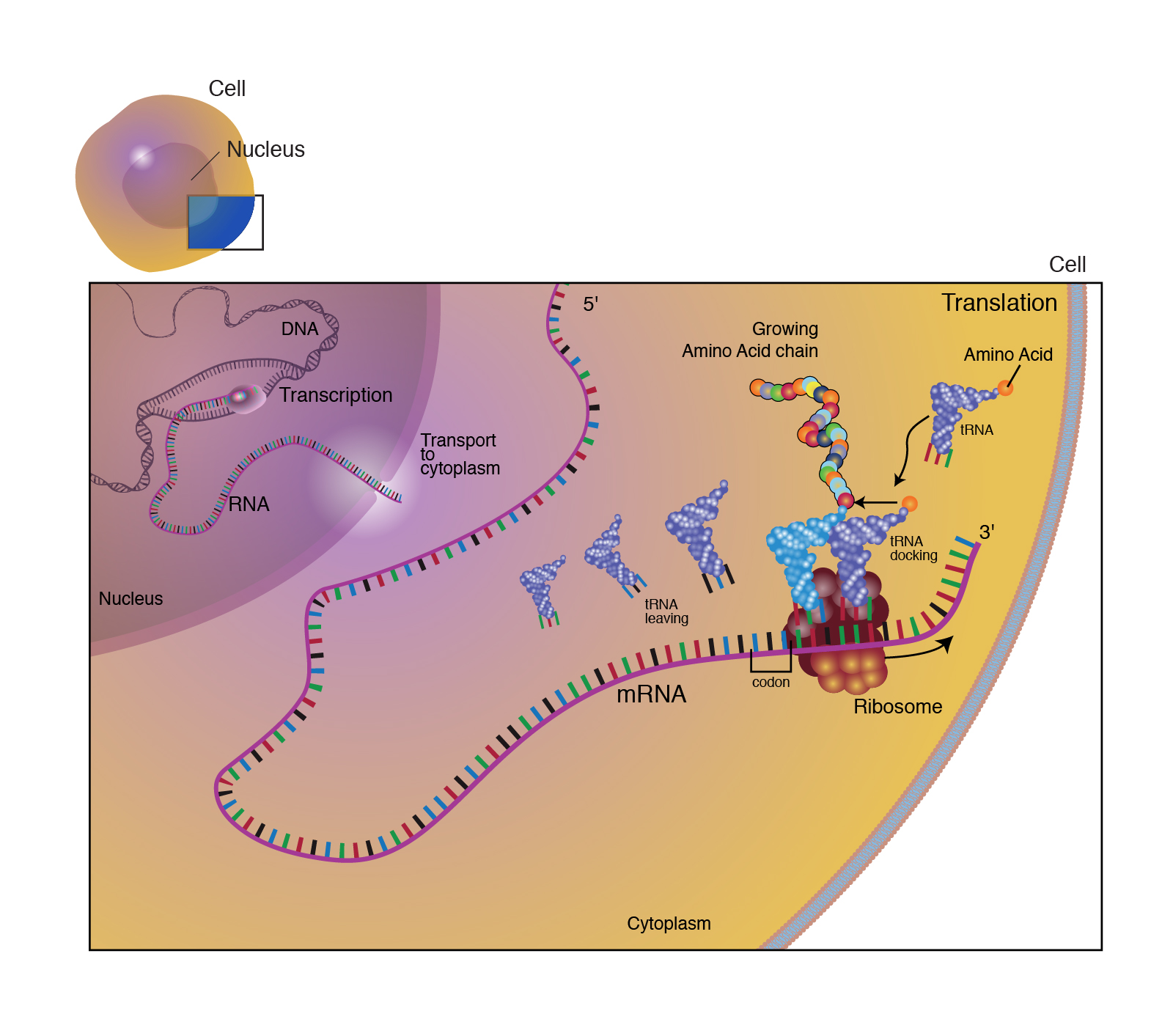

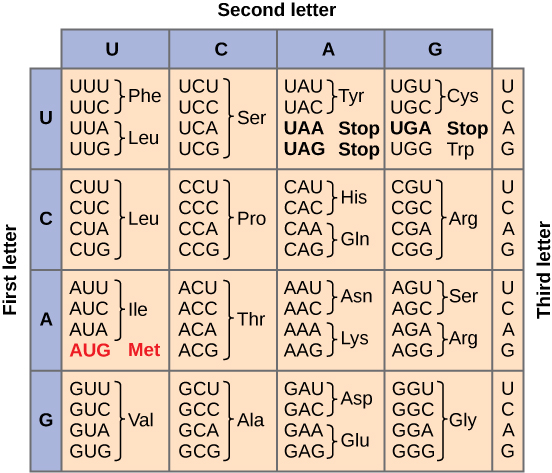

Once mRNA reaches the cytoplasm, the genetic information encoded in the base sequence can be converted into a functional product in a process known as translation (figure 2). The first part of this process is deciphering the information in the mRNA molecule, which is stored in units called codons. Each codon is a set of three bases. As there are four different bases (A, U, C, G), there are 4x4x4 = 64 possible codons. Of these 64 codons, 61 specify 20 unique building blocks of the human body, known as amino acids. The three remaining codons indicate the end of the amino acid sequence (stop codon). Table 1 shows the conversion between codons and amino acids. As there are more codons than amino acids, several codons specify a single amino acid. This means that there is redundancy in our genetic code, the significance of which will be revealed in the next blog!

|

|---|

| Figure 2. Overview of translation. Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute |

The biological machinery responsible for converting codons into amino acids is known as the ribosome. The ribosome itself is a large, complex molecule composed of two subunits (one large and one small). The ribosome facilitates this conversion by matching each codon on the mRNA molecule with its corresponding amino acid. The amino acid is transferred to the ribosome by another RNA molecule, aptly named transfer RNA (tRNA). Along with a specific amino acid, each tRNA molecule has an important region called the anticodon, which is a set of three bases that are complementary to the codon encoding the amino acid attached to the tRNA.

|

|---|

| Table 1. Conversion between codons and amino acids. Courtesy: Openstax CNX |

The first step in translation is known as initiation. In this step the ribosome, mRNA transcript and first tRNA-amino acid come together to form the initiation complex. All mRNAs share the same first codon, which codes for the amino acid methionine. There are three sites in the ribosome where the tRNA can interact, and the first methionine tRNA always docks in the middle (P site). In the P site, the methionine codon and anticodon align.

The next step in translation is elongation, where subsequent amino acids are added. The tRNA carrying next amino acid in mRNA sequence docks adjacent to the initial methionine tRNA in the A site, and binds to its corresponding codon. A chemical bond forms between methionine and incoming amino acid. When this bond forms, the methionine is uncoupled from its tRNA in the P site. This chemical bond between two amino acids known as peptide bond, and chain of amino acids referred to as a polypeptide. The latter term usually reserved for cases where there are more than four amino acids, as two amino acids linked together are known as dipeptide; and three amino acids linked together known as tripeptide. After formation of the peptide bond, the mRNA transcript is shifted along the ribosome by one codon. This shifts the empty tRNA into the E site, and the tRNA carrying the dipeptide into the P site. The empty A site exposes a new codon, allowing the elongation process to repeat.

The final step of translation is known as termination and occurs when a stop codon enters the A site during elongation. The stop codon is recognised by release factors (the stop codon version of tRNA), which interferes with the formation of peptide bonds, and releases the polypeptide from the final tRNA. After being released, polypeptide adopts a unique three-dimensional structure that is determined by the sequence of amino acids. Once the polypeptide has adopted its final conformation, it forms a protein, either by itself or by interacting with other polypeptide chains.

Why transcription?

Making a separate copy of a gene seems inefficient but there is a very good reason transcription exists. DNA is the set of instructions to build all the components of the human body, and all cells in the human body contain DNA. How are there so many different cell variants (e.g. neuron vs. muscle cell vs. bone cell) if they all contain an identical set of instructions? Transcription is the mechanism that allows genes specific to neurons (or any other cell type) to be turned on, whilst ensuring that genes for other cell types remain off.

Not only does gene expression vary across different cell types, but it also varies across time. Let’s use the brain as an example. In early life, the brain grows rapidly – for a baby born on time, brain volume increases 1% per day (ref). Later in life, the brain stops growing but the connections between neurons (synapses) are pruned and refined. Essentially, the human body is characterised by different biological processes at different stages in life, and each of these processes is driven by a unique set of genes. Transcription, or the regulation of transcription, provides a way for gene expression to change across time, as well as different body regions. Let’s look at how regulation of gene transcription occurs.

Regulation of transcription: Introducing non-coding DNA

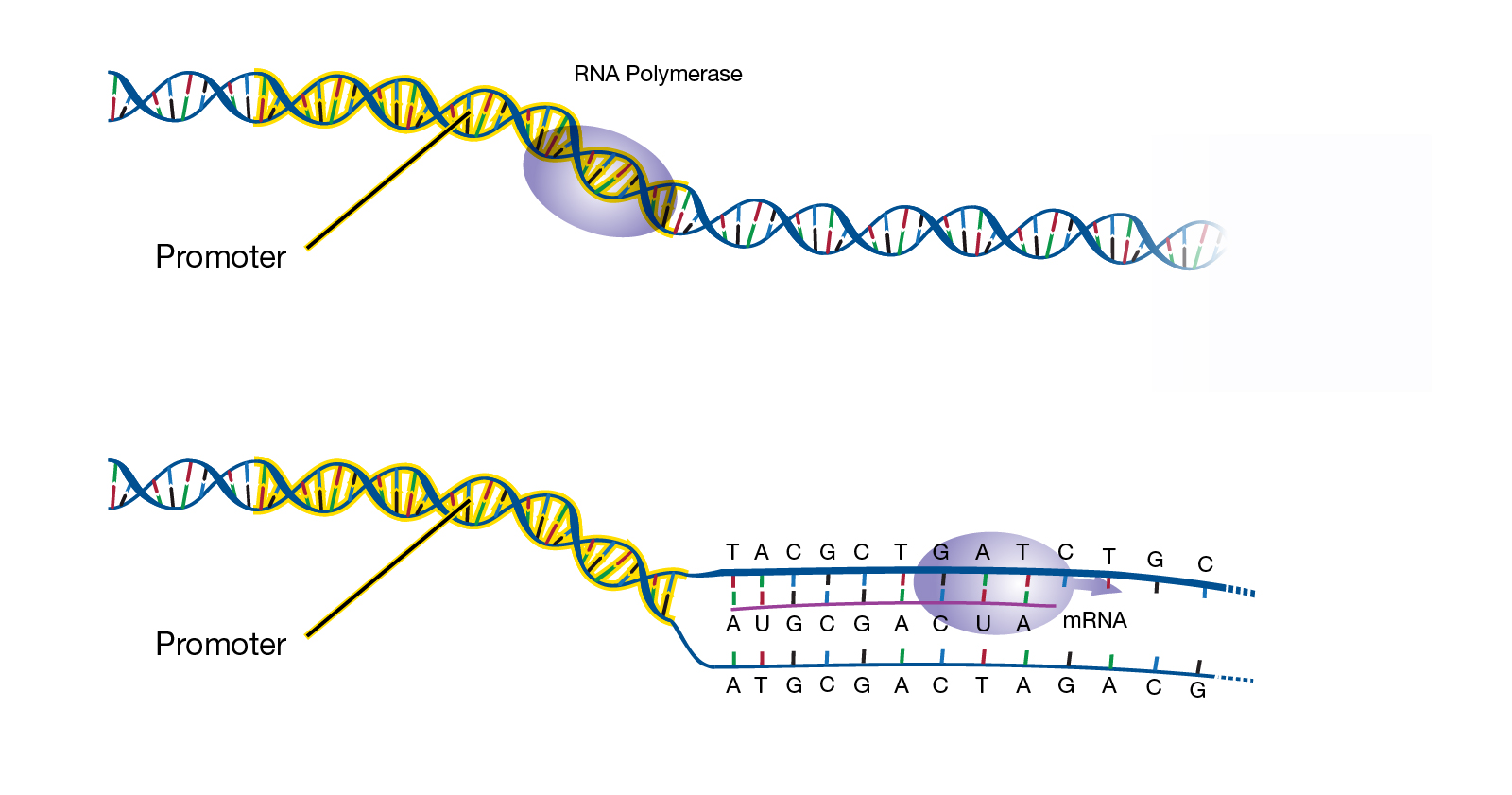

The expression of a gene is initiated when RNA polymerase binds to the gene promoter (figure 3), a sequence of DNA found near the beginning of a gene. This binding process is faciliated by a class of proteins known as transcription factors, which are the primary regulators of gene transcription. More specifically, basal transcription factors are the ones that help RNA polymerase bind to the promoter. But the complexity of biological processes requires gene expression to be more precise than simply ‘on’ or ‘off’. Separate classes of transcription factors, known as activators and repressors, increase or decrease levels of gene expression by binding to separate DNA sequences called enhancers or silencers. Activators and repressors exert their effect by making it easier or harder for RNA polymerase to bind to a gene promoter, respectively.

Before introducing the concept of a gene promoter, I described DNA as though it only encoded proteins. In fact, only ~1% of DNA encodes proteins (coding DNA). The other 99% of DNA (non-coding DNA) is essential for the regulation of gene expression, as discussed above.

|

|---|

| Figure 3. RNA polymerase binding to a gene promoter. Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute |

Regulation after transcription: mRNA processing

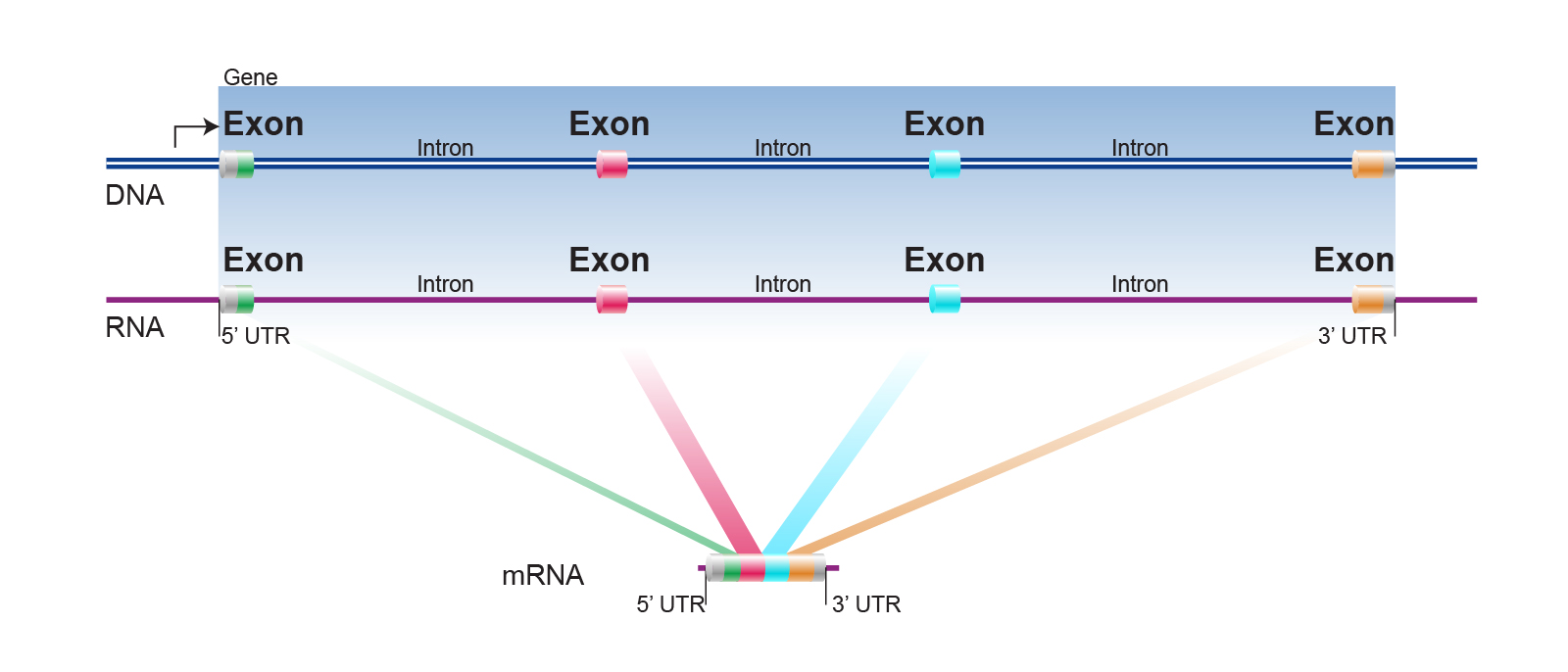

Regulation of transcription occurs even after the synthesis of mRNA. I have explained genes as a contiguous stretch of DNA entirely dedicated to encoding an amino acid sequence. In fact, genes have regions of non-coding DNA scattered through them too! Regions of coding DNA within a gene are called exons, and non-coding regions are known as introns (figure 4). Before an mRNA transcript can be translated, the introns need to be removed and the exons need to be pasted together in a process known as splicing, so that a contiguous polypeptide chain can be produced. The parcellation of genes into exons and introns can be exploited to create different amino acid sequence variations from a single gene in a process known as alternative splicing.

|

|---|

| Figure 4. Introns are removed and exons are pasted together during splicing. Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute |

In this blog, we delved into the processes that convert genetic information into biological processes, and how these processes are regulated. The next blog will explore the mechanism responsible for DNA sequence variation, how these mechanisms can impact protein coding, and how this manifests as phenotypic variation in humans.

Take-home points:

- Transcription produces an mRNA copy of the gene to be expressed

- Translation converts the mRNA transcript into a polypeptide chain

- Gene expression varies across different cell types, and across different life stages

- A majority of the human genome is non-coding, and is important for the regulation of gene expression