Genetics Part III: Mutations & Polymorphisms

Previous blogs have stated that phenotypic variation in humans is due to differences in DNA sequence, but how is this variation produced? The aim of this blog is two-fold:

- Introduce mutations and their consequences on protein coding

- Describe single nucleotide polymorphisms and their role in genetic association studies

Mutations

Although the term mutation is commonly used to refer to a rare DNA sequence variant or phenotype, it also refers to the process of changing a DNA sequence. The human body has a sophisticated set of mechanisms that can detect and repair DNA damage, but sometimes these mechanisms fail for various reasons (read more on this topic here).

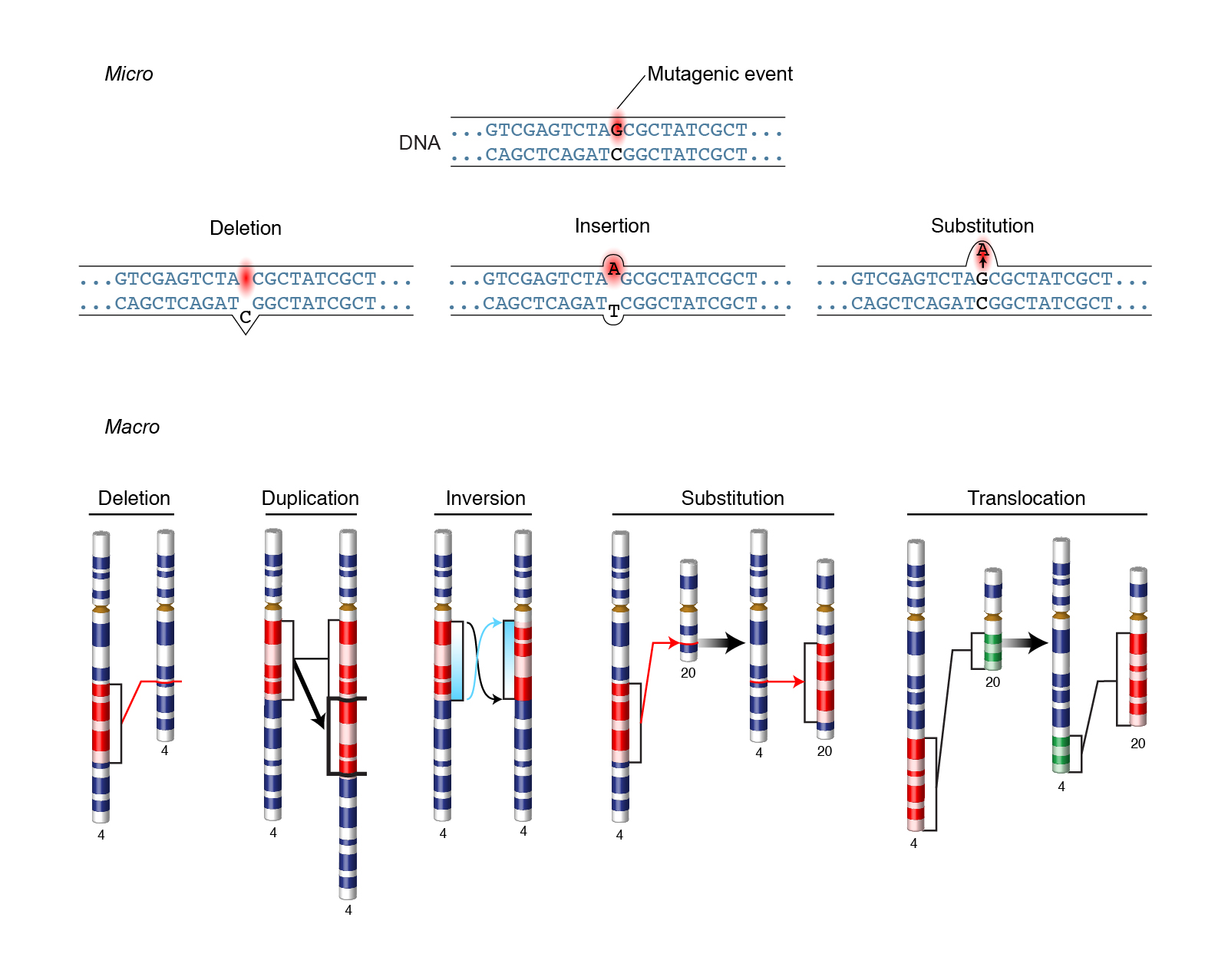

|

|---|

| Figure 1. Different types of mutations. Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute |

There are number of reasons mutations can occur, including:

- DNA copying mistakes made during cell division

- Exposure to ionizing radiation e.g. x-rays

- Exposure to chemicals called mutagens e.g. cigarette smoke

- Infection by viruses e.g. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

There are several different ways that a DNA sequence can be altered. These fall into two groups, based on how they affect the reading frame (the portion of a DNA molecule that, when translated into amino acids, contains no stop codons).

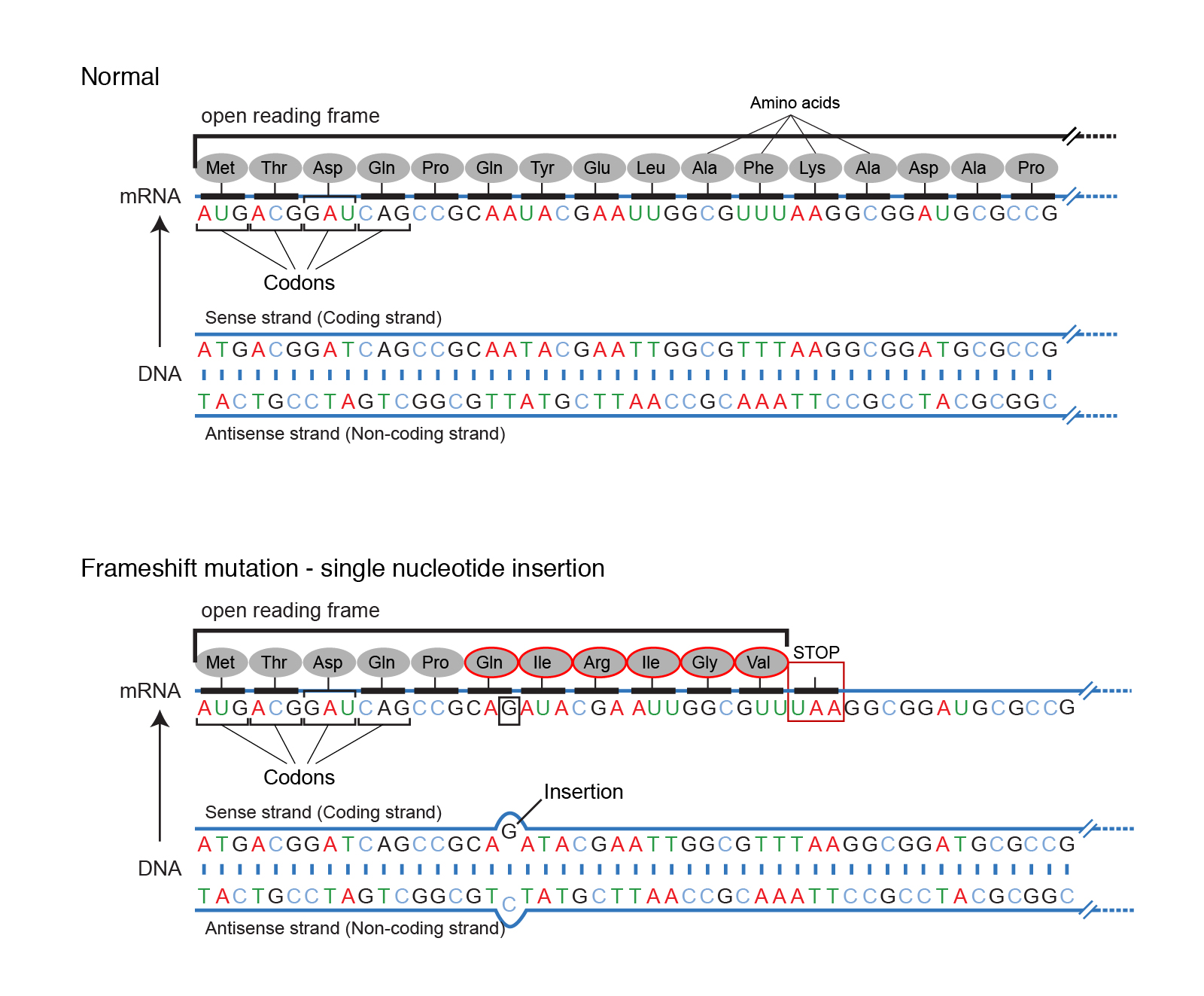

Frameshift mutations

A frameshift mutation is a type of mutation involving the insertion or deletion of a nucleotide in which the number of inserted or deleted base pairs is not divisible by three. The “divisible by three” is important because the ribosome uses codons (a set of three bases) to convert an mRNA transcript into a polypeptide. If a mutation disrupts this reading frame, then the entire DNA sequence following the mutation will be read incorrectly. In some cases the length of the polypeptide is maintained, but in others the polypeptide chain will be truncated as the ribosome reads a stop codon too early.

|

|---|

| Figure 2. Overview of frameshift mutations. Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute |

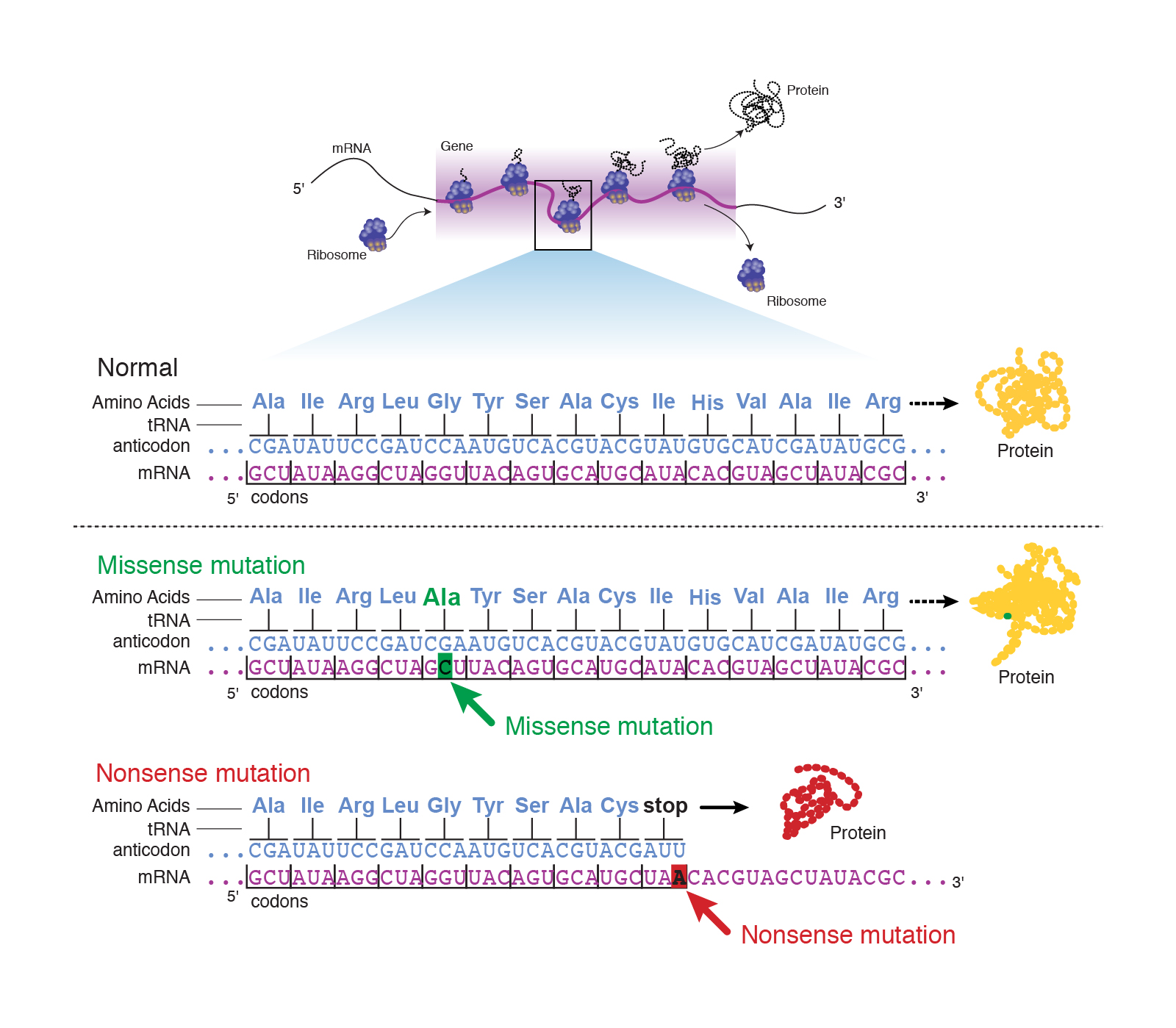

Point mutations

The other class of mutations are point mutation, which describe the substitution of a single base pair. This can have one of three consequences:

- The base substitution can be a silent mutation where the altered codon corresponds to the same amino acid. This is possible because of the redundancy in the conversion between codons and amino acids!

- The base substitution can be a missense mutation where the altered codon corresponds to a different amino acid.

- The base substitution can be a nonsense mutation where the altered codon corresponds to a stop signal.

|

|---|

| Figure 3. Overview of point mutations. Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute |

Mutations vs. polymorphisms

Despite mutation sounding like a negative thing, not all mutations are bad. In fact, the variation that exists between humans is the result of mutations! But we wouldn’t usually refer to common variations between humans as mutations. Instead, we use the term polymorphism. It is important to distinguish polymorphism from allele: a polymorphism is the variation in DNA at a specific site (locus) in a gene that gives rise to a unique gene variant (allele). The threshold for what defines a common variant differs, but a popular threshold is that the less common variant of a polymorphism must be present in ≥1% of the population.

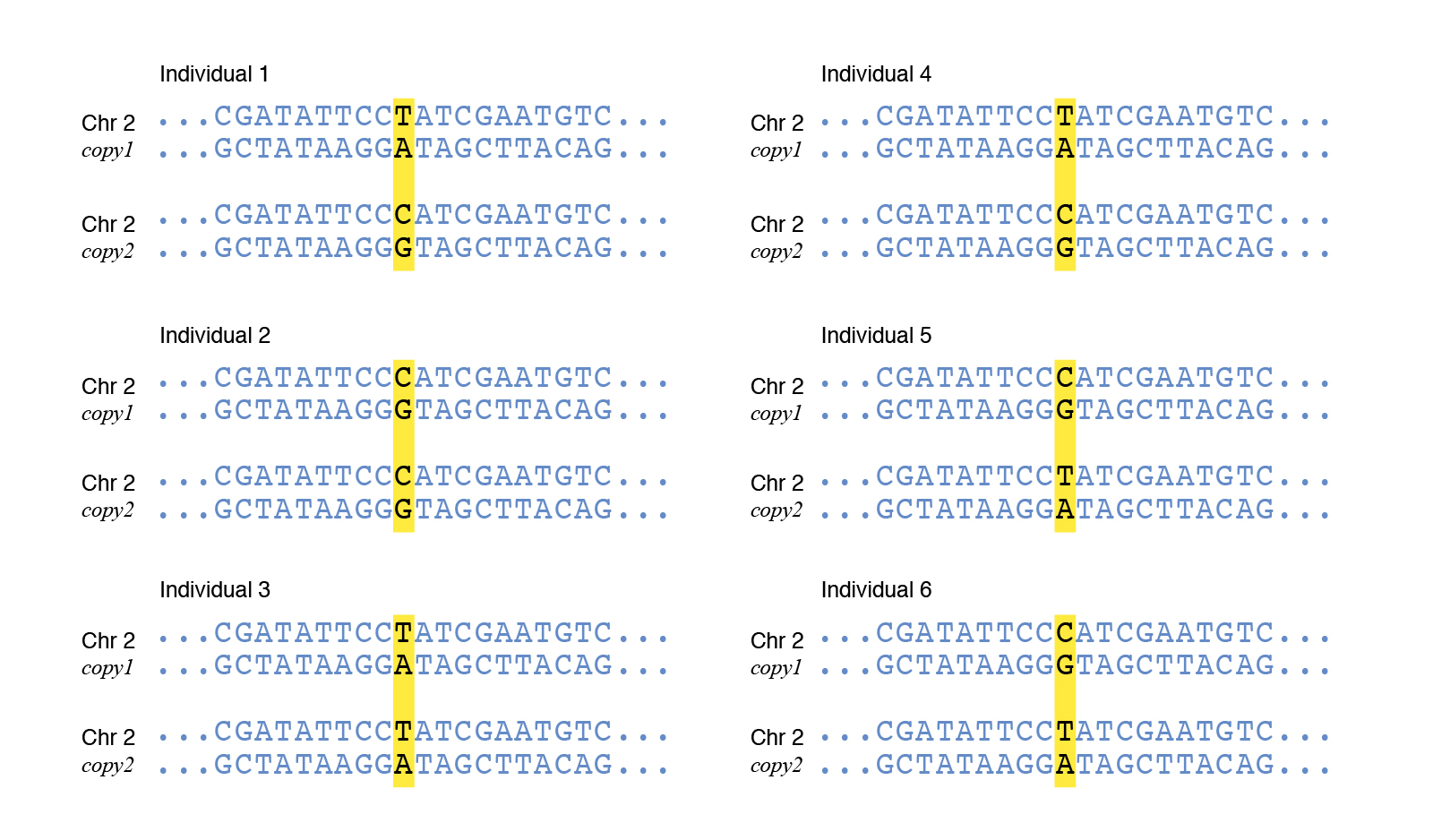

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

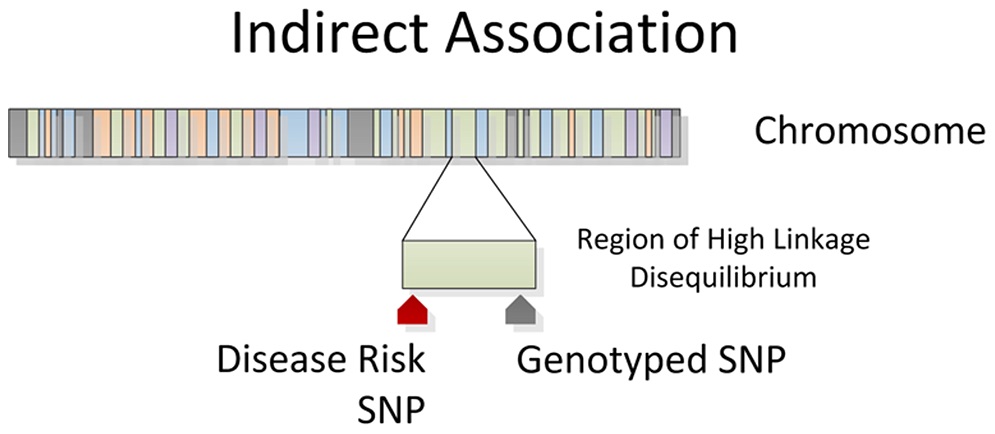

The most common type of polymorphism is known as a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP, pronounced ‘snip’), which occur 1 in 1000 base pairs in the human genome. When describing the frequency of a SNP in the human population, it is usually given in terms of the minor allele (the variant that is less common). Although SNPs can have functional consequences like changes in protein structure, SNPs are more often used as genetic markers in large genetic association studies. The ability to use SNPs as genetic markers is a consequence of a phenomenon known as linkage disequilibrium. But in order to understand linkage disequilibrium, it is important to cover another concept known as crossing over.

|

|---|

| Figure 4. Example of a single nucleotide polymorphism. Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute |

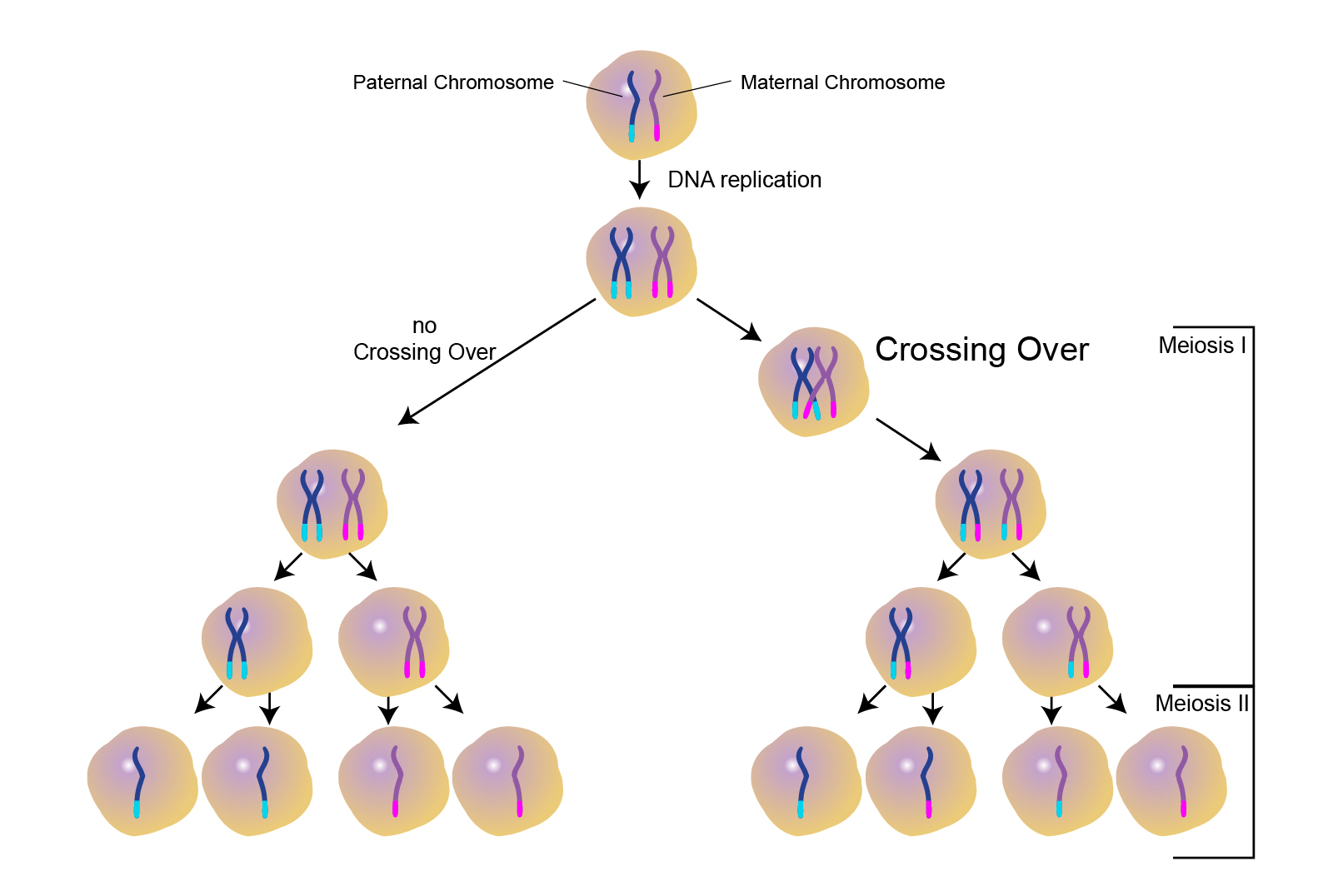

Crossing over

During the formation of egg and sperm cells, paired chromosomes (one inherited from each parent) align so that when the parent cell divides, the total number of chromosomes in the resulting egg or sperm is 23 instead of 46 (figure 5). When this pairing occurs, the chromosomes can become tangled and swap genetic information. This crossing over of genetic information results in new combinations of genetic material on a single chromosome, and is an important cause of genetic and phenotypic variation seen among offspring.

|

|---|

| Figure 5. Crossing over occurs during the production of germline cells (eggs or sperm). Courtesy: National Human Genome Research Institute |

Linkage disequilibrium

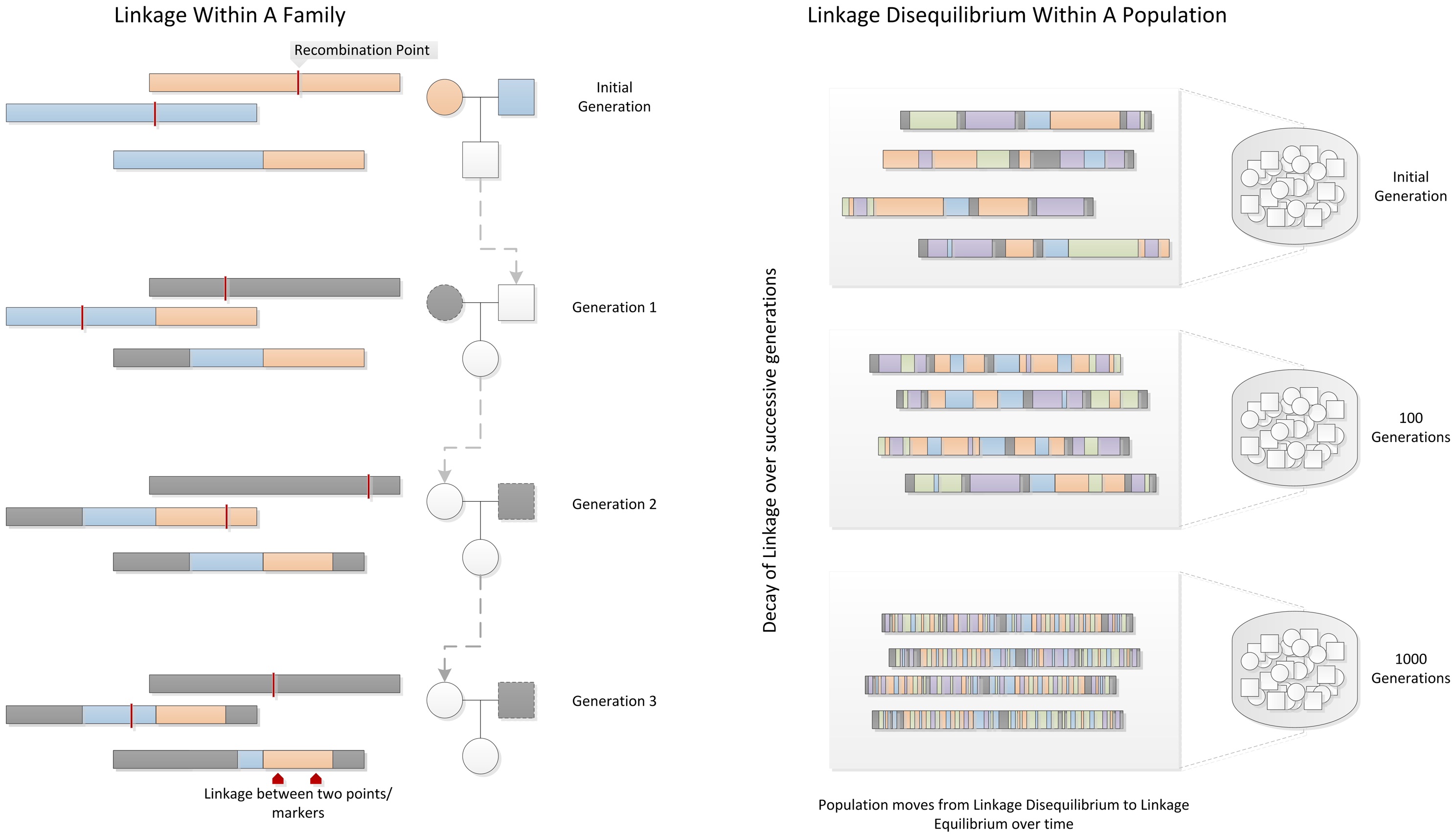

Linkage disequilibrium describes the degree to which a SNP variant is inherited with another SNP variant. If we think about a contiguous stretch of DNA, SNP variants that are closer together are more likely to be inherited together. Alternatively, SNPs that are at opposite ends of the chromosomes are more likely to be uncoupled by crossing over, and inherited independent of one another (linkage equilibrium) (figure 6).

|

|---|

| Figure 6. Decay of linkage disequilibrium in a family (left) and population (right). Courtesy: WS Bush & JH Moore |

The rate at which linkage disequilibrium in a population reduces is dependent on several factors, including:

- Population size

- Number of generations for which the population has existed

- Number of founding chromosomes in the population

The last point is a reference to the founder effect, which is the reduction in genetic variation that results when a subset of a large population is used to establish a new colony. It is referring to the variation in a population when it is founded, rather than the total number of chromosomes in an individual or the population. This means that different human sub-populations have different degrees and patterns of LD. African-descent populations are the most ancestral and have smaller regions of linkage disequilibrium. On the other hand, European-descent and Asian-descent populations were created by founder events and therefore have larger regions of linkage disequilibrium.

|

|---|

| Figure 7. Indirect association between SNP and outcome of interest due to linkage disequilibrium. Courtesy: WS Bush & JH Moore |

It is important to account for population structure when performing large population genetic association studies, because the ability of a SNP to act as a marker in a population will vary according to its ancestral make-up.

Take-home points:

- The term mutation can refer to either the process of changing a DNA sequence, or a rare DNA variant that exists in a population

- Mutations can be broadly classified as point or frameshift mutations, with varying effects on protein coding

- Polymorphisms are common DNA sequence variants in the population that result from a mutation

- Single nucleotide polymorphisms are the most common polymorphisms, and are useful as markers in large genetic association studies