Interpretable Deep Learning Part III: Towards Intrinsically Interpretable Models

In the previous section I analysed state-of-the-art methods of post-hoc interpretability. In this section, I cover some recent methods of deep learning that aim to build interpretability directly into the network architecture, also referred to as intrinsic interpretability. The goal is to develop models that are more interpretable, while achieving a fine balance between interpretability and performance, i.e. the interpretability constraints should not strongly affect the accuracy of the network.

Most methods of intrinsic interpretability are relatively recent and there is an extensive literature of novel methods being developed in this area. In this post, I choose to focus on four types of networks and mechanisms: Capsule Networks, Beta-VAEs, Attention Mechanisms and Interpretable CNNs.

Capsule Networks

The idea of capsule networks (CapsNets) was introduced in the early 2000s, and gained further traction when the method of routing-by-agreement, now used to train these networks, was published in 2017 [1]. CapsNets were developed based on the idea that, in order to improve classification and object recognition, it is important to preserve hierarchical pose relationships between object parts.

CapsNets are built using novel neural units, referred to as capsules. Unlike traditional neural units, each capsule outputs an activity vector, instead of a single scalar. The length of the activity vector represents the activation strength of the capsule, and the orientation of the activity vector encodes instantiation parameters of a specific type of entity, such as an object or an object part.

In training, the outputs from one capsule (child) are routed to capsules in the next layer according to the child’s ability to predict the parents’ outputs. Simply put, the lower level capsule will send its input to the higher level capsule that “agrees” with its input. Following an iterative process, each high level outputs may converge with the predictions of some low level capsules and diverge from those of others, meaning that that parent is present or absent from the scene.

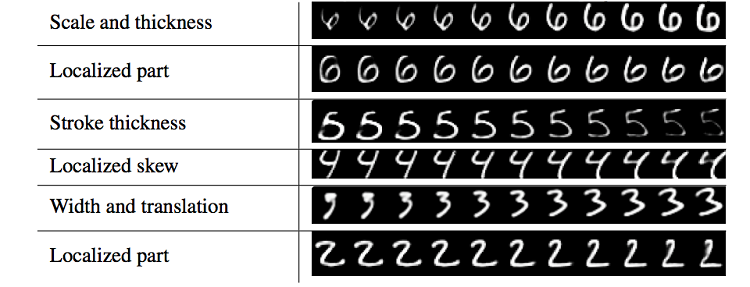

Capsule networks are inherently more interpretable networks than traditional neural networks as capsules tend to encode specific semantic concepts. Experiments have shown that when trained using the MNIST dataset, different dimensions of the activity vector of a capsule controlled different features, including scale and thickness, localized part, stroke thickness, and width and translation.

|

|---|

| Figure 1. Experiments on MNIST showed that different dimensions of the capsules are responsible for encoding different characteristics of the digits. Source: [1] |

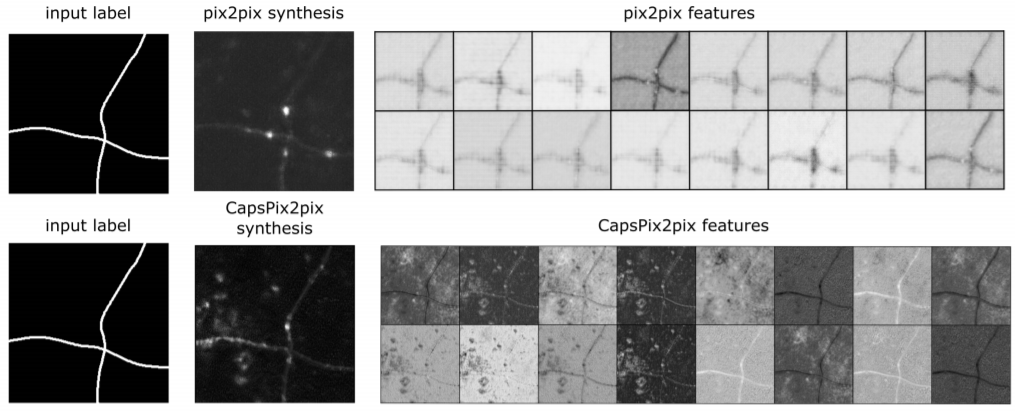

The intrinsic interpretability of CapsNets has been explored for multiple settings, including medical imaging. One main disadvantage of these networks is that they are highly computationally intensive, and therefore cannot be applied (at least with the resources available today) to high-resolution or high-dimensional data.

|

|---|

| Figure 2. Comparison of learned features on the last layer on a convolutional GAN and a convolutional Capsule GAN for image synthesis of cortical axon data. Similar features are shown to be encoded in the same capsule, and different capsules are responsible for capturing qualitatively different features in the images. Source: [2] |

Beta-VAEs

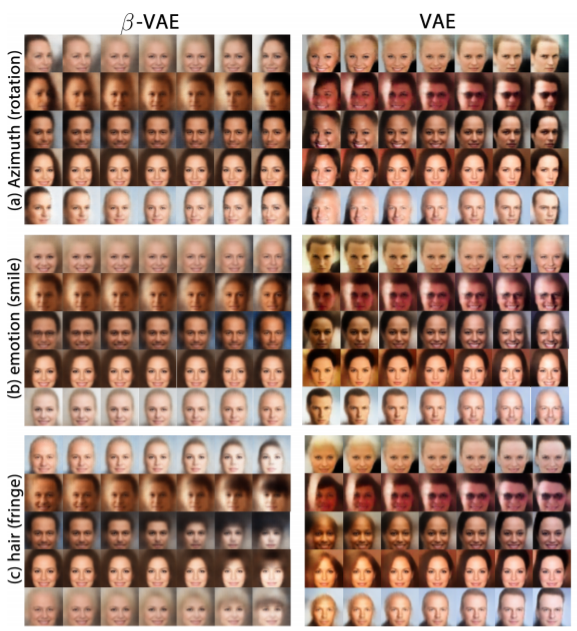

Beta-VAE [3] is a type of variational autoencoder that seeks to discover interpretable, or disentangled, latent representations. It modifies VAEs with an adjustable hyperparameter β that balances latent channel capacity and independence constraints with reconstruction accuracy. In other words, the hyperparameter controls the emphasis on learning statistically independent latent factors. On the celeb-A dataset, for example, the β-VAE was shown to discover, in an unsupervised manner, factors that encode skin colour, transition from an elderly to younger, and image saturation.

|

|---|

| Figure 3. Comparison of disentangling performance of beta-VAE and vanilla VAE. Beta-VAE is capable of learning disentangled factors such as azimuth, emotion and hair, while VAE learns an entangled representation. Source: [3] |

In addition to presenting this method, the authors of the Beta-VAE also devised a metric to compare the degree of latent space disentanglement learnt by different models, termed disentanglement metric score. The procedure to calculate this score is as follows:

- Over a batch of L samples, each pair of images has a fixed value for one target generative factor (for example, scale) and differs on all others.

- A linear classifier is then trained to identify the target factor using the average pairwise difference in the latent space over L samples.

- Smaller variance in the latents corresponding to the target factor will result in an easier classification task, therefore resulting in a higher metric score.

Attention Mechanisms

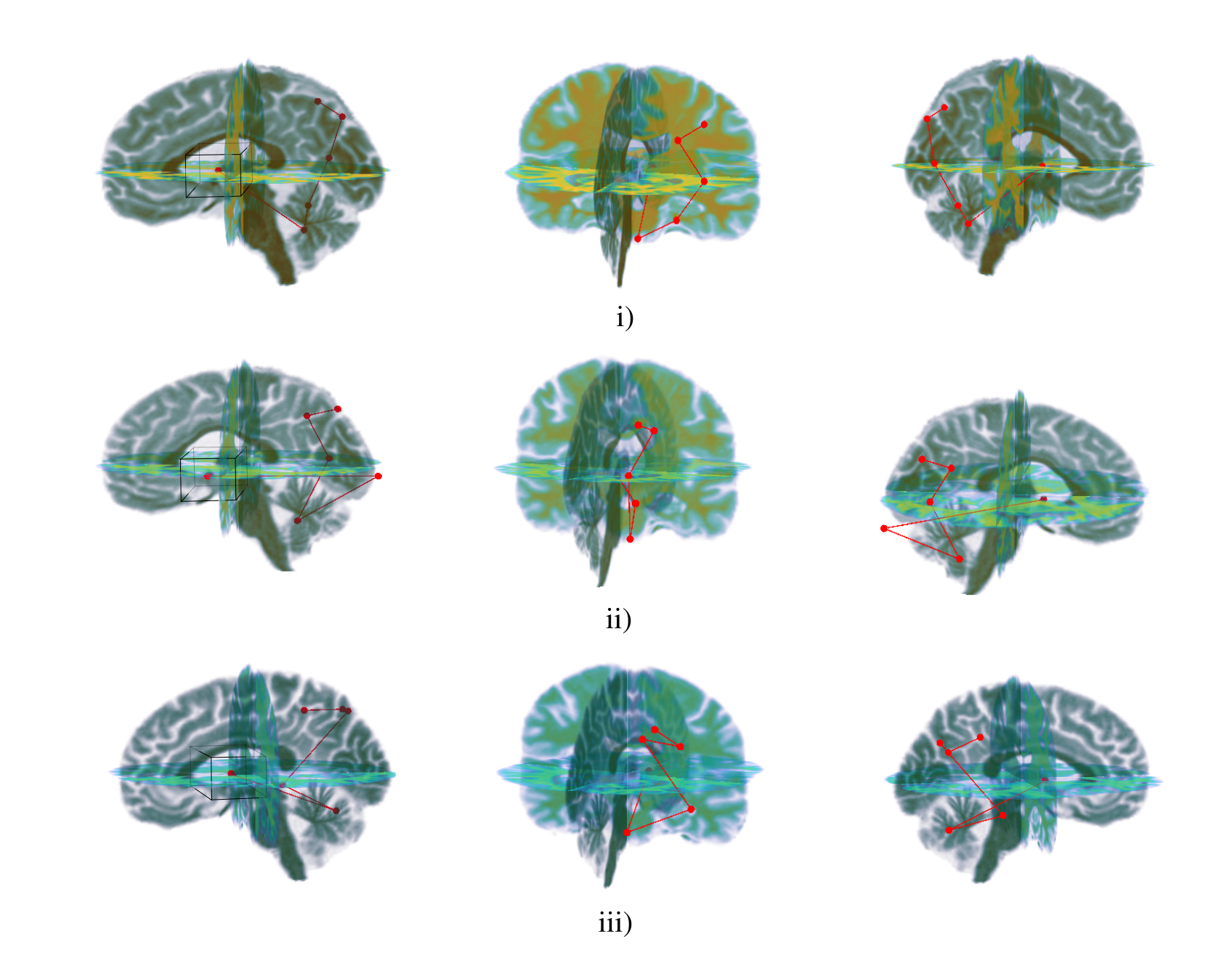

Attention mechanisms in recurrent neural networks can be used as methods of intrinsic interpretability in DL networks. I take as an example NEURO-DRAM [4], a network built around a two-layer recurrent neural network to provide an intrinsic visual explanation of the predictions, in this case on the task of classification of Alzheimer’s Disease.

At each time step t the agent receives a small fraction of the entire image, centred around position lt, and uses this information to decide which location to attend to at the next step t + 1. After a fixed number of such steps, the agent makes a classification decision, receiving at this point a scalar reward determined by its classification accuracy. The goal of the agent is to maximize these rewards along its trajectory, and by doing so it learns to attend to the most informative regions of the image for the task at hand. The path results can therefore be used to “follow” the decisions and create an explanation map of the classification.

|

|---|

| Figure 4. Trajectory taken by the model for classification of Alzheimer’s in three representative brains. By taking this path, the agent attends to regions known to be affected by Alzheimer’s disease, such as the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, lateral ventricles and parietal cortex. Source: [4] |

Interpretable CNNs

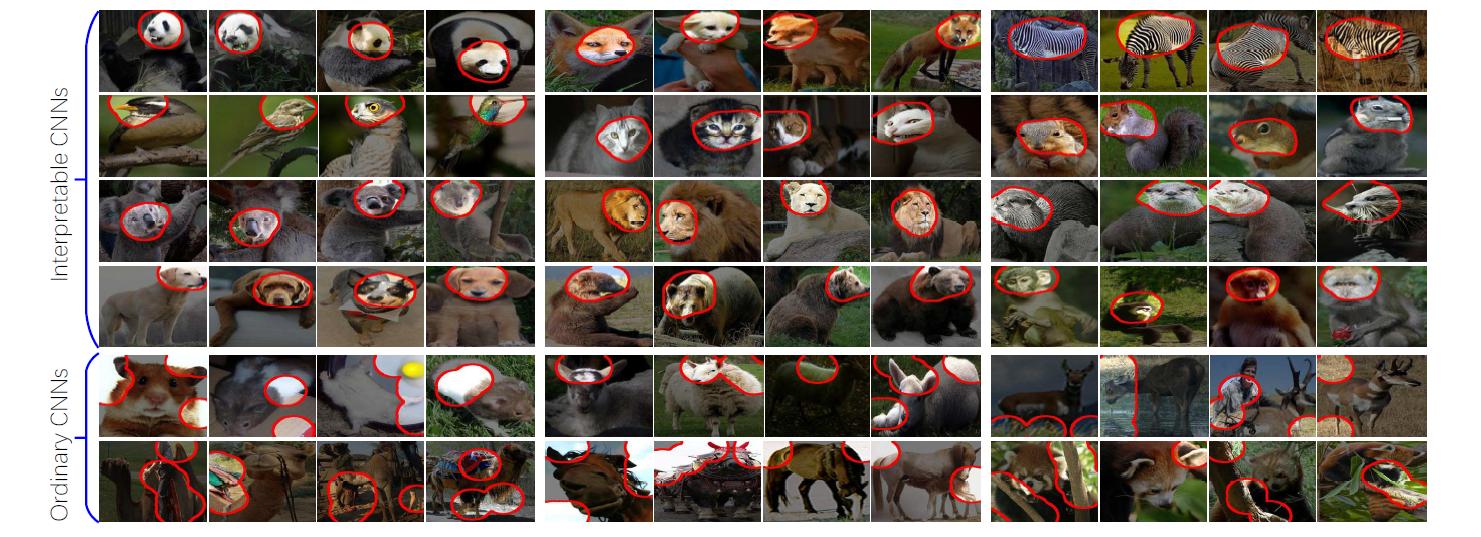

In order to condition CNNs to be more interpretable, Zhang [5] has proposed a method to modify a CNN structure to constraint the last convolutional layers to learn disentangled representations. The authors focus on the last conv-layers as these are more likely to represent object parts. The method works by adding a loss to each filter in the last conv-layers, that is used to regularize the feature map towards the representation of a specific object part.

The method is initiated by designing templates of part location candidates. Each template T is a matrix with the same size of the feature map and describes the ideal distribution of activation for the feature map when the target mainly triggers a specific unit in the feature map. Given the joint probability of fitting a feature map to a template, the loss of a filter is formulated as the mutual information between the feature map and the templates. The loss encourages a low entropy of spatial distributions of neural activations, i.e. the filter is encouraged to activate a single location on the feature map. It also encourages a low entropy of inter-category activations, i. e. each filter in the conv-layer is assigned to a certain category, the category c whose images activate the filter the most. If the input image belongs to the target category, then the loss expects the filter’s feature map to match a template well; otherwise, the filter needs to remain inactivated. The study assumes that if a filter repetitively activates various feature-map regions, then it is more likely to describe low-level textures (e.g. colors and edges), instead of high-level parts.

|

|---|

| Figure 5. Visualization of filters in top layers in interpretable CNNs and in ordinary CNNs. The interpretable CNN is shown to usually encode head parts in its top layers, when trained for classification of animals. Source: [5] |

Merging intrinsic and post-hoc interpretability

From the advantages and disadvantages of both post-hoc and intrinsic methods that were already discussed in these posts, it is easy to visualize that such methods could be combined.

This type of framework was explored by Zhang [6], by proposing the construction of a decision tree to explain CNN predictions of interpretable CNNs. i.e. the decision tree explains which filters in a layer are used for the final prediction and how much they contribute to the prediction. The procedure is as follows:

- As in the example above, the interpretable CNN learns filters to represent object parts.

- Then, each filter is assigned with a specific part name and decision modes are mined to explain how the CNN uses parts for prediction, to build a tree.

- Each node in the parse tree quantitatively explains the prediction at a different abstraction level, clarifying how much each object filter contributes to the prediction score.

This is just one example of how these two types of methods can be combined. Taking advantage of the “best of both worlds” with intrinsic and post-hoc methods - for example by analyzing disentangled features with a post-hoc framework - is a direction that shows a lot of promise for interpretability of CNNs.

Summary

In this series of posts, I gave an overview of the need for interpretability in deep learning and methods that have been designed for this purpose. With a focus on computer vision tasks, I explored some popular post-hoc methods, taking into account its advantages and shortcomings. I also analysed a few examples of methods that attempt to achieve, to an extent, intrinsic interpretability of networks.

This is not, by any means, an extensive exploration of all methods of interpretable and explainable AI. For more on this subject, I strongly recommend the book Interpretable Machine Learning by Christoph Molnar, that explores different methods of interpretability in ML for different types of data.

It is important to note that interpretable deep learning is still a recent topic and, as I mentioned, there is still not a unified or formal definition of what interpretability entails, or how it should be measured. As this field of research grows, it is important that researchers also develop methods that can be used to evaluate interpretability and quality of explanations (taking into account the different types of users for which they are meant to) and this way be able to evaluate and compare different interpretable methods.

Finally, causal explanations and causal inference in deep learning were not explored in this review, as the topic requires a more in-depth analysis, and will therefore be the subject of my next series of posts.

References

- Sabour, S., et al. (2017). Dynamic routing between capsules. Advances in neural information processing systems.

- Bass, C., et al. (2019). Image synthesis with a convolutional capsule generative adversarial network. International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning.

- Higgins, I., et al. (2017). beta-VAE: Learning Basic Visual Concepts with a Constrained Variational Framework. ICLR.

- Wood, D., Cole, J., & Booth, T. (2019). NEURO-DRAM: a 3D recurrent visual attention model for interpretable neuroimaging classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.04721.

- Zhang, Q., Nian Wu, Y., & Zhu, S. C. (2018). Interpretable convolutional neural networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition.